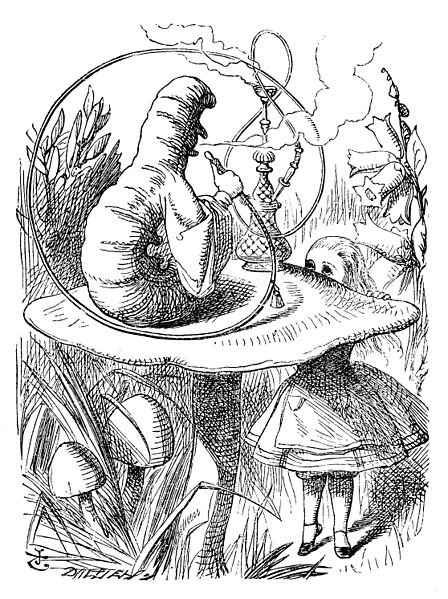

‘“I can’t explain myself, I’m afraid, sir,” said Alice, “because I’m not myself, you see.”

“I don’t see,” said the Caterpillar.”’

– Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Leukaemia, cancer; there are definitely many downsides.

The chemo makes you feel pretty grim. You’ve got a steady supply of poison being pumped through your veins. It kills off the malignant cells – or so you hope – and obliterates a good many healthy ones in its wake.

But if we leave aside all the physiological drama for a moment, all the aches and pains, the crippling nausea and the weakness, there’s one thing I really dread. To be honest, given the choice, I’d prefer an injection (a little subcutaneous one though, nothing overly invasive).

I’m referring to the moment of revelation. The bit where you have to tell someone for the first time.

It could be a close friend, it could be an old colleague. It could be the alumnae office from university, ringing up to see what you’re doing with your life. It’s always fraught with tension.

You do everything in your power to avoid the loaded silence. First you drop the bombshell, then you sense the utter panic on the other end of the phone; their brain goes into overdrive, ticking away furiously searching for the right words. You start talking and talking, you keep talking; you don’t let them get a word in edgeways. You’re trying to spare them the unease. It becomes a matter of boosting morale. You find yourself gushing about impressive remission statistics with all the aplomb of a failed head teacher boasting about exam grades.

When the numbers look good it gives you something to hide behind. It’s just a question of finding the right numbers. It’s not easy when there aren’t many to go on. There are only 28 recorded cases of my cytogenetic anomaly in the UK. Sixteen of them, I was told in the vaguest terms, responded to treatment. I don’t know what happened to the other 12.

But nothing stands in my way. I’ll do anything to avoid the shocked pause. On more than one occasion, I’ve found myself spinning out stories and statistics, ending the conversation with the conclusion that, really, I’m incredibly fortunate – in fact, more than that, I’m actually ingenious; I’ve somehow managed to contract the best, most treatable disease in existence, in all the ideal circumstances, surrounded by the greatest support and finest medical facilities possible. And it’s perfect timing as well. (‘Imagine if I’d been born a few decades earlier! I wouldn’t stand a chance!’)

But if it’s hard for me, it must be much more difficult for the other person to find the right thing to say. And there is no right thing to say. There are plenty of wrong things. I have some stunning examples.

More on that next time.