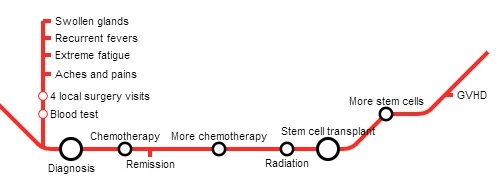

On the Cancer Underground, you can take the Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia line. I don’t recommend it, personally. Lots of delays, frequent disruption and constant complications (especially if you have a stem cell transplant). Only 40% of passengers make it out alive.

But back to where it all started. Here I am, out of breath, faint, waiting in A&E, expecting a jab in my arm. Blood test and then take the bus home.

The registrar. She looks at the swollen glands in my neck. She winces.

‘Haven’t you been to your GP?’

‘I did. They said swollen glands are normal.’

‘That doesn’t look normal to me.’

I’m told to wait in a side room. No one comes. I go out looking. Outside are corridors, a bustle of men shifting beds on wheels. I head back to the waiting room. Toddlers clawing at the skirts of their mum’s hijab. A man sits on his own as blood gushes from his nose. He holds a toilet roll to his nostrils to soak up the flow. The entire roll is drenched red.

A boy of about 12 in a wheelchair waits patiently next to his dad. A couple of porters approach them, apologetic. ‘We urgently need a chair. Is it alright if we borrow yours for a minute?’

The boy smiles, nods. His dad helps him out and onto one of the seats.

Eventually I find a nurse. She frowns at me. ‘You should be on your own.’ She leads me back to the side room.

‘What’s going on?’ I ask.

‘I don’t know what to say,’ she says. ‘Your haemoglobin levels are 5.’

I’m sorry?

‘They’re half what they should be.’

She runs off to attend to someone. I keep waiting. A man comes in and pulls me by the arm. ‘Right you, off for the kidney scan!’

What?

‘You are Maria, aren’t you?’

A few hours later I’m taken to an isolated room on a ward upstairs. I’m put on a drip. Fluids. The rest follows in my mind like a montage from a film. Because only in films have I seen drips and machines and medical equipment. A blood transfusion. More fluids. Scans. Needles. I remember the needles, the hurtling pain, the probing. A shifting panel of different nurses try and fail to insert cannulas in my veins, to give transfusions, to take blood. Cannula, I say now, over a year later, because I know the word. It was only another needle then.

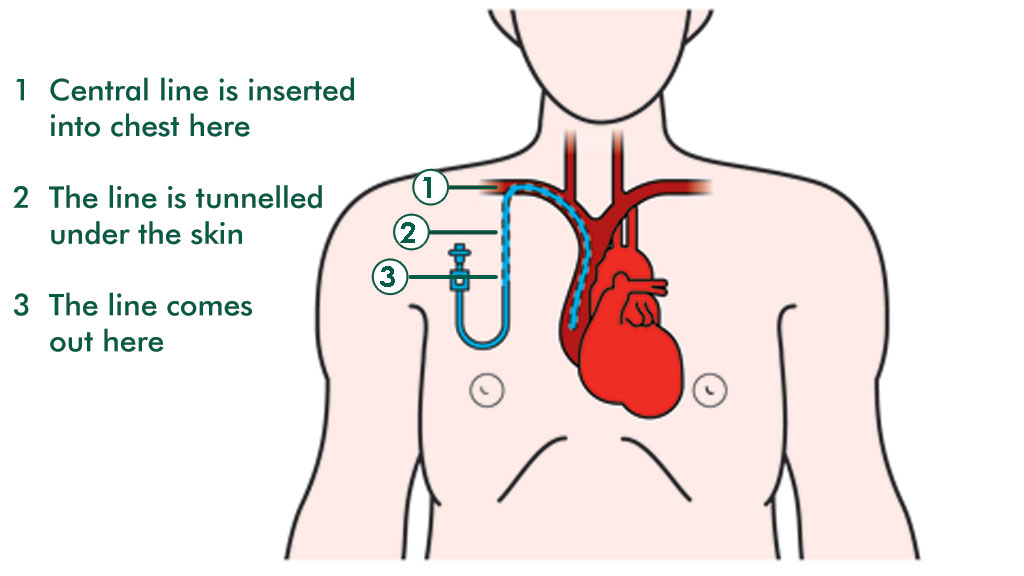

Back then cells were rooms in prisons. If I heard the words ‘Central line’ I thought of the red stripe across the Underground map, not a tube inserted under the skin of your chest.

When three doctors arrived the next day, and shook my hand, and shook my mum’s hand, and told me I had leukaemia, they might as well have been speaking another language. They had waited for my mum to arrive before they gave me the diagnosis. They were very careful, very polite. They handed me a Macmillan booklet and left us alone together to ‘talk things over’.

I looked down at the booklet – ACUTE LYMPHOBLASTIC LEUKAEMIA in green letters. It hadn’t entered my mind that there might be different types of this disease.

‘Leukaemia,’ I said to my mum. I was 22, I had heard of it before, obviously. ‘How is that related to cancer?’