I didn’t write anything for a long time this year because I was too ill. There have been a lot of ‘hiccups’.

Except I don’t think anyone’s ever had to take morphine or undergo serious surgery for their ‘hiccups’. It’s the kind of term a well-meaning medical professional would use to describe the past year since my transplant. No sign of relapse so far, no organ failure. Still alive. Never once been in intensive care. For a transplant patient I’m ‘lucky’.

I don’t feel it, most of the time. But I’ve seen what ‘unlucky’ looks like.

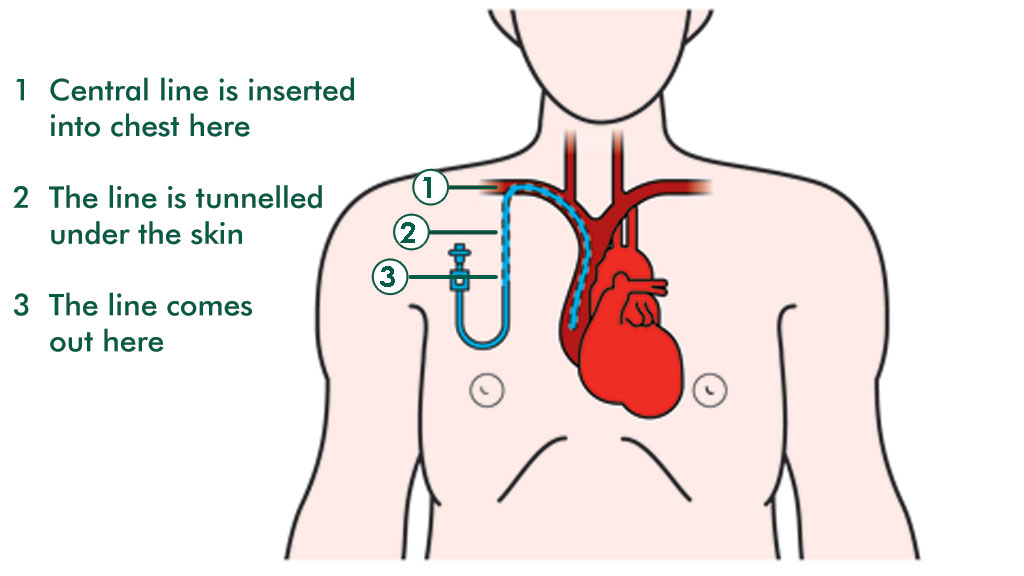

The first time I met Sunny was in the transfusions suite at my hospital. It was a few months after my transplant. I still needed regular top-ups of red blood and platelets to keep me going.

In walked Sunny asking for a blood test; big brassy blonde wig, black leather jacket, jeans. As I sat there with my bag of platelets ticking away, we got chatting. I recognised her face. While I was in isolation I used to see her every day, from my window on the ward. Sitting on a bench in the sunshine with her chemo drip, cannula in one hand, cigarette in the other, surrounded by friends and relatives, usually at least a dozen of them. She came from a big Catholic family; I found out later. I remember her now from that time – a bald girl in a red polka-dot dress, chain-smoking, laughing – looking pretty carefree, for someone hooked up to a bag of poison.

I’d assumed she was around my age, in her twenties. But she told me she was 33. She had two teenage daughters. She’d been diagnosed with ALL, like me. We had the same consultant too – she called him Dr Horror, she told me with a laugh.

She had just had her second bone marrow transplant – she’d only been discharged from the ward a couple of days earlier. I was incredulous. After one transplant I could barely string a sentence together, and still months later I felt barely alive. But here she was after two, yakking away, chatting about the whole thing like it had been a particularly stressful holiday in Ibiza and then the flight delays were a nightmare and she just wanted to get home now and have a bath and a cup of tea.

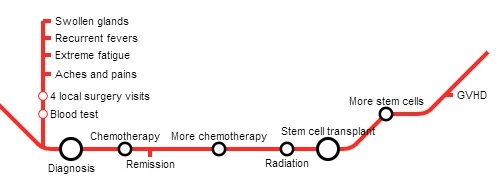

She was talking. I couldn’t keep up. ‘It took ages to get diagnosed. First I thought I had flu, then I felt so tired I couldn’t get out of bed for weeks and then my GP wouldn’t see me. I went to her and she said I had depression but I knew it wasn’t. I kept going back. Then she refused to see me. The same GP who’s known me 30 years. I’ve been through two pregnancies with her. She didn’t want scans or nothing…

‘I had a transplant from my sister but it was too good a match, too close to my own bone marrow, like identical twins they said, so I relapsed. And then the doctor here’s telling me I have six weeks to live and I should be making my will and I’m not going to see my daughter’s 16th birthday. But I said no. I pleaded with them to give me another transplant and they kept saying they wouldn’t do it. They said it would kill me.

‘But I’m not giving up that easy. I begged for another chance and then they found a donor in Germany. And then he went missing. He disappeared. They literally could not get hold of him. By this point they were saying I had a few days left if they couldn’t find a donor.

‘But they found another donor in the end. The transplant was worse this time round though. They couldn’t put a line in me, it kept getting infected. And I couldn’t have total body irradiation again so I had twelve-hour chemos, with a cannula. I went blind for a few days. They thought I’d had a stroke. That was the worst. I couldn’t see my girls. But, you know, I’m still here.’

The nurse came over with Sunny’s blood results. I was shocked – a bit envious – that her counts were all decent levels; she didn’t even need a transfusion.

That was it with Sunny. She was invincible – implausibly unaffected by all the ravages of the nuclear-force treatment that she’d been hit with. She was like one of those lovable cartoon characters that inconceivably springs back to their original self – no matter how many cartoon cliffs they fall off or cartoon cats devour them whole, they’re always back in one piece for the next episode.

I bumped into Sunny on most of my clinic visits. She was friendly with everyone, she called everyone darling. She talked a lot about her daughters, with a fierce matriarchal pride. She was a single mum, and she made it clear that she didn’t stand for any mollycoddling; in her house there was hard work and discipline. Her eldest was going to study law at university, she said.

She talked about her struggle to eat, the appetite loss and the nausea. I noticed her getting thinner and paler. She stopped wearing her wig. She complained of back pain. The doctors sent her off for scans.

It turned out the cancer had spread to her spine.

I knew that the prognosis was not encouraging. But whenever I saw her I said ‘you’ll be alright’. Her confident response every time – ‘I’ll be fine’ was enough to convince me.

One day I was admitted to the ward with a virus, something that happens from time to time. Because my immunity is so low, my body can’t fight off infections by itself – it needs strong intravenous drugs. I had a bed on the bay, with two elderly ladies, and Sunny opposite me. She was meant to be starting chemo the next day. She had suffered a stroke a few days earlier and lost the sight in one eye; she was wearing a patch over it, like a pirate. Her head was completely bald. She said prayers; she had a string of rosary beads. She was weaker than ever. Her mouth downturned at the corners, her speech was slurred. But she still managed to slip outside every now and then for a cigarette.

‘Where have you been?’ One of the elderly ladies asked. ‘Seeing your boyfriend?’ We all laughed.

I remember, later, Sunny lying on her bed while a doctor tried to persuade her to have a feeding tube inserted. She protested. She wanted to eat. She still craved eggs and bacon, she said. He kept insisting: ‘The muscles in your mouth are too weak now to chew anything.’ I remember wishing he’d leave her alone. I couldn’t see the point in prolonging her suffering.

And still I never really believed she would die. Here was a woman who’d defied medical expectations so many times, outlived the predictions, laughed death in the face. So when I was admitted again to the ward a couple of months later, I asked if Sunny was around.

‘She passed away a few weeks ago.’

I felt like laughing. It was a joke. I knew how ill she was but she couldn’t die. She couldn’t be talking and smoking and laughing one day, and dead the next. She was in hospital for god’s sake. You don’t die in hospital – not if you’re only 33, my brain said. They have intensive care units, there are resuscitation methods. In a modern hospital there is every substance and mechanism imaginable to keep you alive: blood transfusions, oxygen, CPR, insulin, dialysis, IV antibiotics.

There are drugs – there are so many drugs – drugs to salvage every kind of organ failure. This is 2014, they don’t just let you die – she’s 33, she has her girls to look after, they need their mum, how can she not be alive. You’re not meant to go until decades later, when you slip away peacefully in your sleep.

I write all of this because I’m sick of hearing that cancer is a battle that teaches you strength, and you’ll come out the other end a better person (if you come out the other end at all.) I’m sick of hearing someone say they survived cancer because of their positive attitude: ‘I never once believed I was going to die. And that’s what got me through it.’ Or, patting the head of a chuckling toddler: ‘It’s this little chap that kept me going. I knew I had to stay around for him.’

Because dying isn’t a decision, and the fight for survival is not a fight which the more defiant are destined to win. I think of Sunny now with her rosary beads, as I last saw her – staunchly convinced that her God would show her mercy. But it doesn’t matter how relentlessly optimistic you are. Cancer doesn’t care about your mental strength, cancer doesn’t give a toss how much you meditate. Cancer, as someone once told me, is an indiscriminate fucker.

And despite my pessimism and my cynicism, I’m still alive. And on my visits to clinic, there’s still one face I half-expect to see. ‘Alright darling. Yeah I’ll be alright.’

‘”I’ve had such a curious dream!” said Alice, and she told her sister, as well as she could remember them, all these strange Adventures of hers.’

‘”I’ve had such a curious dream!” said Alice, and she told her sister, as well as she could remember them, all these strange Adventures of hers.’