Cancer, when it’s curable, is like North Korea. At times the prospect of imminent danger slips from your mind, and it fades into a dormant kind of fear. It is terrifying. But you don’t think it’s going to kill you. It becomes a nebulous constant in the background. At times you can even laugh about it.

Then suddenly it’s threatening you with missiles.

Or false alarms. You never know.

There are certain anecdotes you don’t want to hear first thing in the morning from a burly man equipped with a full set of needles, when you’re receiving blood transfusions and a nice batch of platelets before breakfast.

‘Girl in this room,’ the nurse told me. ‘10 years ago. Serbian. They were going to deport her. There were lots of delays. Then they tried a stem cell. The treatment wasn’t working.’

I didn’t know what to say.

‘In this bed here,’ he continued with a smile. ‘I remember it like yesterday. Such a nice girl.’

He stopped for a moment, cradling the packet of blood in both hands, then began again:

‘She was given three months to live.’

I felt cold.

He paused for effect.

‘She recently finished her degree. She’s a practising lawyer now.’ He was digging out his phone. I saw lots of hair and smiling teeth. ‘There she is with her fiancé.’

Not everyone, though, can manage to confront mortality and then raise a smile within the space of a few moments. I know that most people have the best of intentions, but some of the cack-handed questions and comments I’ve come across are stultifying. The ambulance driver who asked me brightly, with a big grin, ‘What are you going into hospital for?’ I had been diagnosed with leukaemia an hour earlier. I was in tears at the time. Or the message I received from a former university friend, some weeks ago, after posting several links to this blog on my personal page (as well as an accompanying explanation): ‘Hi Hannah, are you not well?’

Then there’s irony. Often best considered the privilege of the patient. I remember the smug-looking medical student who came in to examine me, bent my elbows at lots of awkward angles and asked too many questions, until a certain picture of a virtuous healthy lifestyle began to emerge. Never eaten meat, light drinker, keen swimmer and runner, tried a handful of cigarettes at most.

He threw his arms up in sarcastic lamentation. ‘Why, Hannah, why?’

On the other hand, I don’t mind being told how inordinately brave I am. It does scare me a little, though. It all seems very ominous. I feel like asking, do you know something that I don’t? I thought the prognosis was encouraging.

The same goes for all the tower of inspiration rhetoric. I don’t agree, but I lap it up anyway. Or people praying for me.

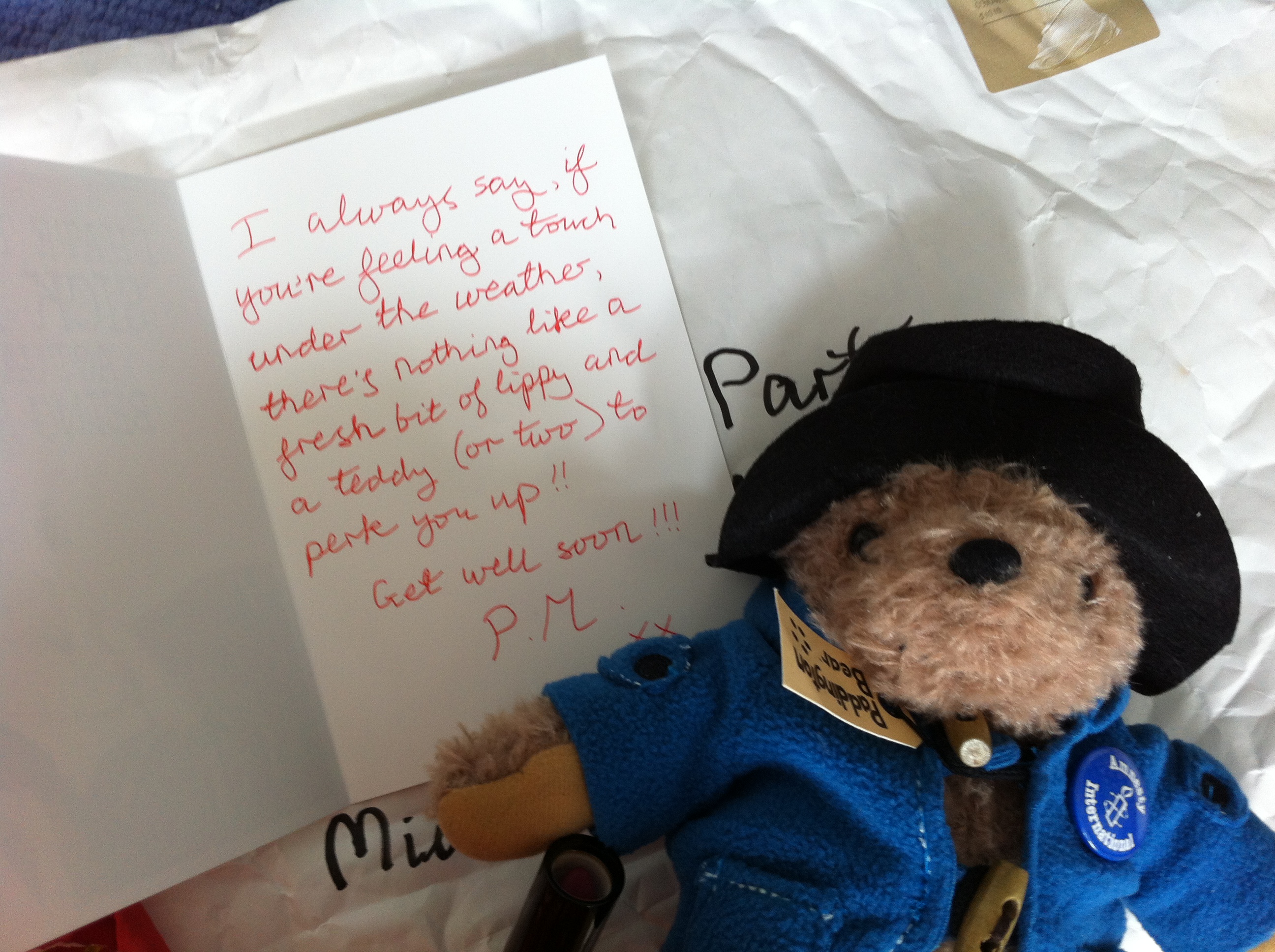

But when there’s any doubt over what to say, an anonymous gift never goes amiss. I’m still trying to establish who sent me this. Thank you to the mystery sender: